Words, when written, crystallize history; their very structure gives permanence to the unchangeable past. –Francis Bacon, essayist, philosopher, and statesman (1561-1626)

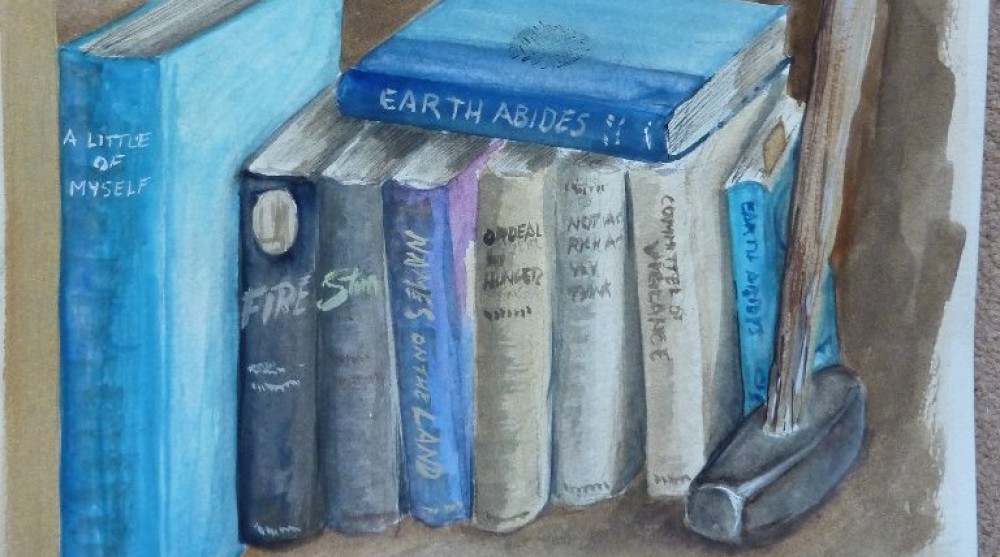

George R. Stewart’s Names On The Land was published in 1945 just as World War II ended. In a letter to Stewart, his friend, Pulitzer Prize Winner Wallace Stegner, jocularly said he was interested in reading the book to see if GRS had included some of the more salacious names on the American land or if he’d cleaned them up so as not to offend the blue noses. Stewart was name-honest in the book, but discreetly so.

Today, however, that approach would surely result in loud protests over his description and explanation of the origins of American place names.

There is a wave of censorship about place names and an avalanche of renaming not unlike the practice in Orwell’s 1984 of changing history and word meanings on a frequent basis: Done for political reasons and ignoring the effect on the history of our nation and our times.

Some names are clearly insensitive, and no one should oppose such renaming. But many names which WE have made derogatory were in their original meanings only descriptive. If the naming bluenoses insist on sanitizing them to the detriment of their true meanings it would be unfair to those who originally used them. Much better to modify them so the original meaning is clear.

“Squaw,” for example, originally meant “young woman” or woman to Algonquin and other indigenous peoples; when immigrants began flooding here certain of them made the word a slur; but to deny the honest name is to give the racists who changed its meaning another nasty victory over those first American peoples by corrupting their language. If “Squaw Valley” is offensive, re-name it “Young Woman Valley.”

Place names are also often used to honor people who at particular times in our history had a profound effect on our nation and our world. Sometimes their influence is seen as glorious; sometimes, in hindsight, as dangerous. Yet in removing “Washington” from the maps because he owned slaves we also remove reminders of him from our history. Ironically, that could mean other countries who’ve honored the man who led our fight for independence would be celebrating him but Americans would forget who he was.

One especially egregious example is the current attempt to remove Joseph LeConte’s name from the land. LeConte and his brother John were Georgians who owned slaves during and before the Civil War. Extremely racist, they supported the Confederate war effort. After the rebels were defeated the LeContes moved west to California. Excellent scientists and university administrators (they’d been professors in a southern university) the brothers were quickly hired by the new University of California to provide strong academic foundations for the new school. It was a sound decision – John LeConte, Physicist and UC’s first President, established a physics program that would eventually lead to the discovery of new elements of matter – two of which, Californium and Berkelium are named for the University. Californium is at the heart of many smoke detectors.

John’s brotherJoseph LeConte was a beloved geology professor, botanist, and namer of species, who with his close friend John Muir and a few others founded the Sierra Club. The good work done by the club and its inspiration for the modern environmental and public lands protections movements are achievements on a summit of the greatest human accomplishments – like the Declaration of the Independence, written by another slave owner, Thomas Jefferson. Yet the 21st century Sierra Club, which owes its existence to Joseph LeConte, has “unnamed” the Lodge in Yosemite Valley which was built by the contributions of Sierra Club members and UC faculty and students to honor LeConte.

There was also an attempt to tar John Muir with the brush of racism. The true danger of Orwellian renaming is this: If those who founded the Sierra Club were racists, why, the Club may be a racist institution, so its arguments and programs for preservation of wild places can be ignored.

There’s a name for this kind of argument in debate circles: “Ad Hominem” – “To the man” – in which you turn a question of fact into a slander on an individual or an organization to cloud the evidence for the other side’s (stronger) case.

Another problem with such Orwellian “unnaming” is that it allows history to be forgotten. As George Santayana wrote, Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

In the Lake Tahoe and Carson Pass area, many features and places are named for Civil War people and events. Fredricksburg (a massive Confederate victory), Burnside Lake (named in jest by former southerners?) for the Union General who lost the Battle of Fredricksburg), Jeff Davis Peak (named for the President of the Confederacy), Reno (named for a fallen Union General). Those names are messages to help future scholars piece together the connections between the Lake Tahoe area and a Civil War thousands of miles away.

The proper way to deal with offensive names or names which carry an offensive history behind them is to add a plaque or addendum on the map explaining why they are offensive and that they’ve been left so people will know their history and not repeat its mistakes.

George R. Stewart was aware that such unnaming could happen, and he cautioned readers against it in Names On The Land: “The classical interests of the later eighteenth century are as much part of the history of the United States as are the existence of the Indian tribes or the Revolution. To maintain, as many have done, that Rome and Troy are mere excrescences on our map, is to commit the fallacy of denying one part of history in favor of another part–or else is to be ignorant of history.

“The ideals and aspirations of the Americans of that period deserve their perpetuation.”

In a similar way, Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, and Sarah Botstein wrote in the LA Times (9-11-22):

Do Americans today have the courage to look at the mistakes of our past for the sake of our improvement? Courage, in this case, includes our willingness to teach our entire history, to confront the difficult along with celebrating the positive. ….

…“If we’re going to be a country in the future, then we have to have a view of our own history which allows us to see what we were,” historian Timothy Snyder told us. “And then we have to become something different if we’re going to make it.”

***************

Centuries ago, Thomas Jefferson wrote …a name when given should be deemed a sacred property….

George R. Stewart would heartily agree. Fortunately, through his writings on place names – some in his books, some now preserved in hidden places – future scholars will be able to discover why we named places for certain things or certain people at certain times. And while they will surely wonder at our glorification of the ignorance of our own history, they will honor George R. Stewart for his celebration of Names On The Land.

This is an incredibly complicated subject especially when you consider that no one has ever been pure good. No person who lived in history is clean enough for some people and to others, everyone is dirty and we should name it after birds and trees.

But it isn’t a simple issue. We don’t need to keep everything — or remove everything. We need to keep some things and get rid of others, but it needs to be done with thoughtfulness, understanding and a knowledge of history — as well as the recognition that no matter what you do or how you do it, it will never satisfy everyone.

Good, thoughtful comment, Marilyn.