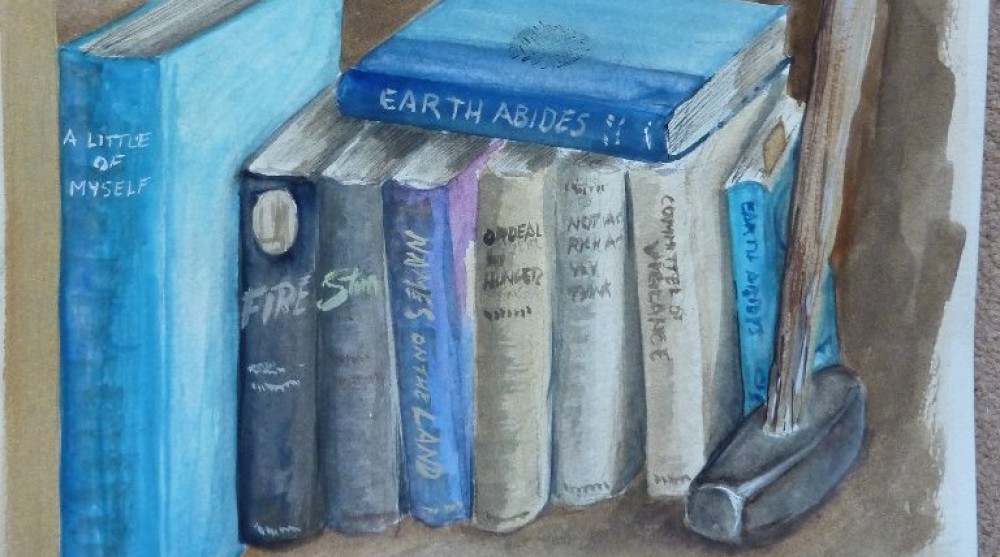

Wallace Stegner’s fine essay, “George R. Stewart and the American Land,” originally written for a re-issue of Stewart’s Names On The Land is now more easily found in Stegner’s last work, Where The Bluebird Sings To The Lemonade Springs. Written a year after Stewart’s death, the essay is a consideration of Stewart and his work. But the focus is on Stewart’s unprecedented work about American place-naming. In another essay, Stegner described Names on the Land as an unprecedented book – “Nobody ever wrote a book like this before…” fine praise from a great writer, who recognized the quality and uniqueness of Stewart’s book.

Stewart described the book like this: “There’s no model for that book… It is absolutely on its own.” Others had collected the meanings of place names. But no one before Stewart had attempted to write a national history of place-naming – that is, a history which explained why we Americans chose to name places in certain ways at certain times in our history. As usual, Stewart wrote the book with the general literate reader in mind, as well as the scholar, so although it is meticulously-researched, the book is also beautifully written and easy-to-read.

It begins, thus:

Once, from eastern ocean to western ocean, the land stretched away without names. Nameless headlands split the surf; nameless lakes reflected nameless mountains; and nameless rivers flowed through nameless valleys into nameless bays.

Read those opening words and you know the author has done his share of historical research, and he understands the music of language.

Stewart begins with the words of Those Who Preceded Europeans, the Native people – the people whose names still sprinkle the land, east to west, from Massachusetts to Mississippi to Tuolumne, and north to south from Dakota to Arkansas to Acoma. As each different language group settles, and sprinkles names on the land, he tells their story.

Names often reflect culture. The Spanish usually named places for the Catholic saint whose day was being celebrated on the day the Spanish “discovered” the place. The San Andreas Fault is so named because the Portola Expedition found a small lake in the fault valley on the feast day of Saint Andrew. The French also named for Saints – St. Louis – but also for more earthy things – Grand Tetons. Americans heading west by wagon, however, were more practical, naming landmarks in a way that would help those who followed: Pilot Peak was a landmark to steer your wagon toward, but Stinking Water Pass was not the place to drink or fill water containers (you waited for the next pass, Sweetwater).

In some cases, original names were so modified by later settlers that original meanings are lost – “Purgatoire River” became “Picketwire” to the cowboys, for example. In the mixed American culture, names often combined languages’ words and grammar – thus “the Alamo” and Paso Robles (rather than the proper Spanish name, “El Paso de los Robles”).

When all was said and done, we had names to inspire us, and the world. Many of the names were so beautiful in sound and spelling, and so poignant in history, that they became legendary: Golden Gate, Yosemite, Florida, Montana, the Grand Canyon, the Painted Desert, Route 66, Mt. Shasta, Death Valley, the Great Plains, the Colorado River, the Rio Grande, the Missouri, Hollywood, Annapolis, and on and on. Others were simple American names, often given with a touch of good American humor. Bug Tussle, Cutlips, Accident, Nameless, Difficult, Nipple Butte, Show Low, Weedpatch, Punkin Center, and their kin are spread across this land.

Stewart’s book was a major success, even inspiring a program in the literate radio detective series, “The Ghost Town Mortuary” in The Casebook of Gregory Hood. (An actor portraying Stewart helps Hood locate a kidnapper’s hideout when he identifies the one-word message from the victim as the name of a town.) The book has been reprinted several times, most recently by The New York Review of Books Press.

Stewart once said that Names on the Land would never be translated because of all his books it was the most specific to our nation’s use of plac name words. But if current plans work out, it is going to be translated, into Chinese. Translator Junlin Pan, and Meng Kai, Geographic Editor of China’s most prestigious publishing house, Commercial Press, have accepted the challenge. The Chinese people are deeply interested in America – in how we have accomplished what we have accomplished – and are trying to learn as much about our culture as possible. Names on the Land is certainly as good an introduction to American culture as anything every written, so it’s a good – if difficult – work to translate.

I’m sure that if George R. Stewart were alive he would be following the Chinese publishing project with keen interest. Of all the books he wrote, Names on the Land was his personal favorite. It was as challenging for him to research and write the book as it will be for Junlin Pan to do a translation that captures the nuances, the cross-linguist nature, and the wry humor of the names on our land, as sung in Stewart’s fine book. I wish Junlin Pan and the Commercial Press all the best, and I wait with bated breath for the result.